The last three years have been difficult. The pandemic crashed cargo volumes, then cargo volumes surged. It scrambled supply chains and tested the ability of the logistics industry to keep our economy moving. All of that happened with the pandemic sickening our communities and decimating our labor force.

Through all of that, the supply chain was largely successful. Strangely, while the next few years are likely to be less difficult, I expect that as an industry we are also less likely to be successful. In times of crisis, it is almost easy to focus on what is necessary to keep the ship from sinking. The next few years will not have same sense of crisis and will likely not motivate stakeholders to address what will be serious threats to the health of the supply chain that begins with the ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles.

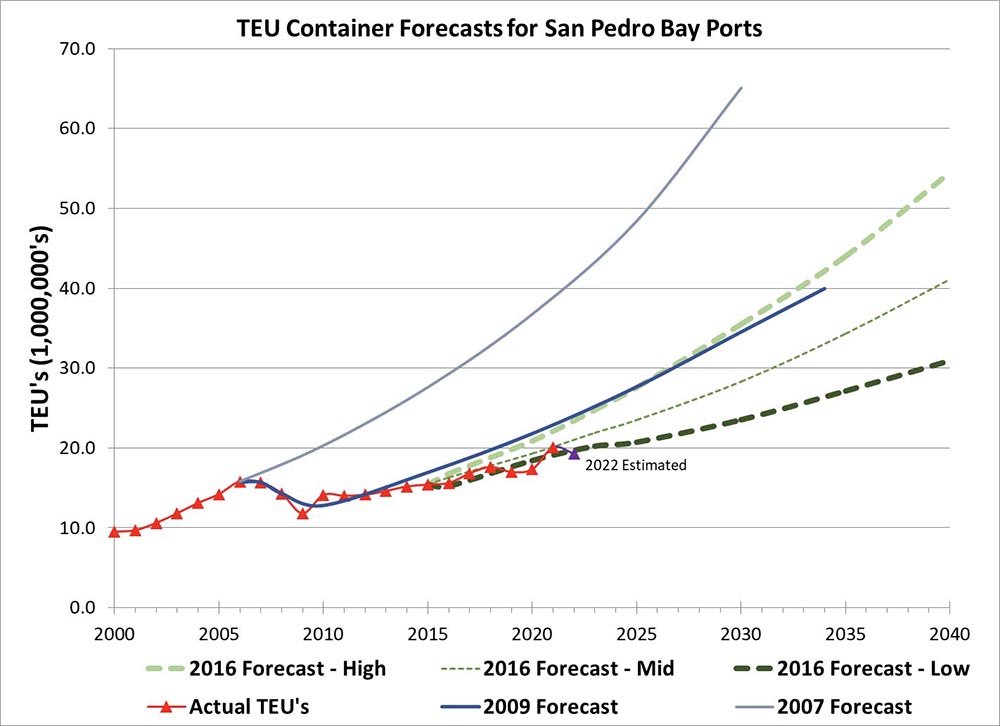

Over the course of the pandemic, cargo surged by 14.3% from the pre-pandemic high in 2018 of 17.5 million twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs) to 20.0 million TEUs in 2021. It was noted with joy that that surge brought the San Pedro Bay ports’ cargo volumes from underperforming the “Low Forecast” of the 2016 cargo volume, which was a downward revision of the 2009 forecast (which in turn was a downward revision from the 2007 forecast), to in line with the “Mid Forecast.”

Unfortunately, the surge—which meant our ports were only just meeting six-year-old expectations—is now going out with the tide. Without the pressure to push goods into the country through the closest international gateway to east Asia, cargo owners are beginning to select other gateways.

It will be the fight against this diversion of cargo that will be the challenge for the next several years. Already, the San Pedro Bay ports will be ending 2022 down compared to 2021. Based on current volumes, a decline of over 3% is likely. That will have San Pedro Bay again underperforming the “Low Forecast” of 2016.

This is not a decline in cargo volumes due to a decline in post-pandemic consumer demand. Consumer demand remains strong, but not through California ports. For 30 years, the Los Angeles and Long Beach ports have had the No. 1 or No. 2 position, occasionally switching places, for container throughput in North America.

For the first time since 1992, the Port Authority of New York/New Jersey (PANYNJ) is likely to claim the No. 2 spot—and will be in spitting distance of No. 1. PANYNJ has already claimed the top spot for August and September in 2022. In August, the Port of Los Angeles was down 15.6% and the Port of Long Beach was flat (down 0.1%), while PANYNJ grew 8.0%.

And in September, the Port of Los Angeles was down 21.5% and Port of Long Beach was down 0.9%. PANYNJ grew 16.3%. As of the end of September, PANYNJ is already the No. 2 port in the country based on year-through-September cargo volumes. If PANYNJ continues strong through the end of the year, the Port of Long Beach will be bumped to the no. 3 spot for the first time in 30 years.

Already, October is looking good for PANYNJ. The Port of Los Angeles is down 24.8% and Long Beach is down 16.6%. While PANYNJ’s October numbers are not yet available, even if they are just flat for October, the no. 1 spot is theirs again. What is more likely is that they will post strong growth. At the time of this writing, it’s not impossible at this point, though very unlikely, for PANYNJ to finish the year in the No. 1 spot, which last happened in … I don’t know, my spreadsheet only goes back to 1990.

As cargo goes, so goes jobs, economic activity, tax revenue and vibrant communities. Not only does that cargo represent economic activity that supports the livelihoods of longshoremen, truckers and others in the supply chain, it is also the means of financing the transition to zero emissions.

So, the challenge for the next several years must be competitiveness. Competitiveness will preserve our jobs, our communities and fund our future development.

The Los Angeles and Long Beach ports have done a yeoman’s job of advocating for resources to improve California’s competitiveness. Their role as developer is critical to a successful future. But development is only one element of our collective competitiveness. We also must look to California’s policies that support or harm our ports.

It cannot be just the ports and port stakeholders that advocate, plan and build for competitiveness. California continues to adopt policies that add friction and reduce competitiveness. Unfortunately, that looks set to continue. Without a crisis to sharpen the focus, it is likely that California’s leadership will quickly forget the role of its ports in our economy.

Thomas Jelenić is a vice president with the Pacific Merchant Shipping Association. He works with policy makers, regulators, industry leaders and other entities to help ensure that sound science and industry issues are part of the discussion.