Without a concerted effort to change the trajectory of offshore wind port investment, the U.S. is likely to fall short of both its short term goal of creating 30 GW of new renewable energy by 2030 and long-term goal of 110 GW by 2050.

This is according to Darren McQuillan, vice president of global business development with Bardex Corp., a Northern California company that designs, builds and supports engineering systems and propriety products for the marine industry.

His comments were made during one of the sessions held during the Floating OSW (Offshore Wind) Port & Vessel Summit that took place Feb. 22 in Sacramento, Calif.

The summit was held by Oceantic Network, a Baltimore, Md.-based network of companies and individuals focused on tapping the vast renewable energy resources that lie offshore in the world’s oceans.

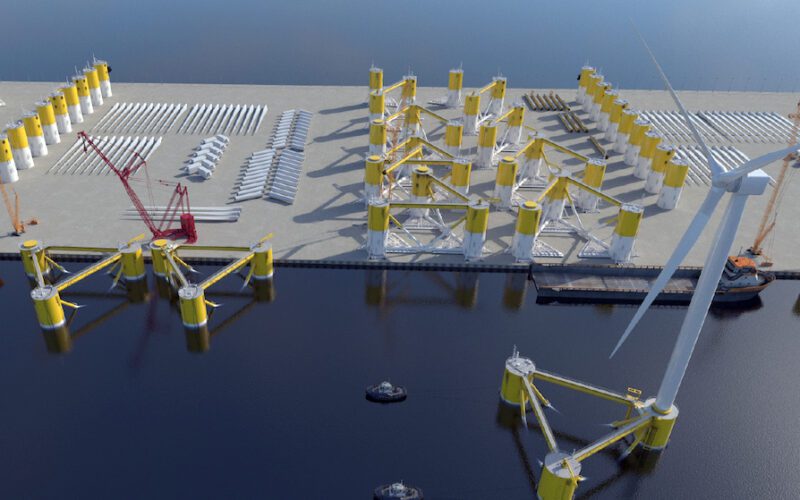

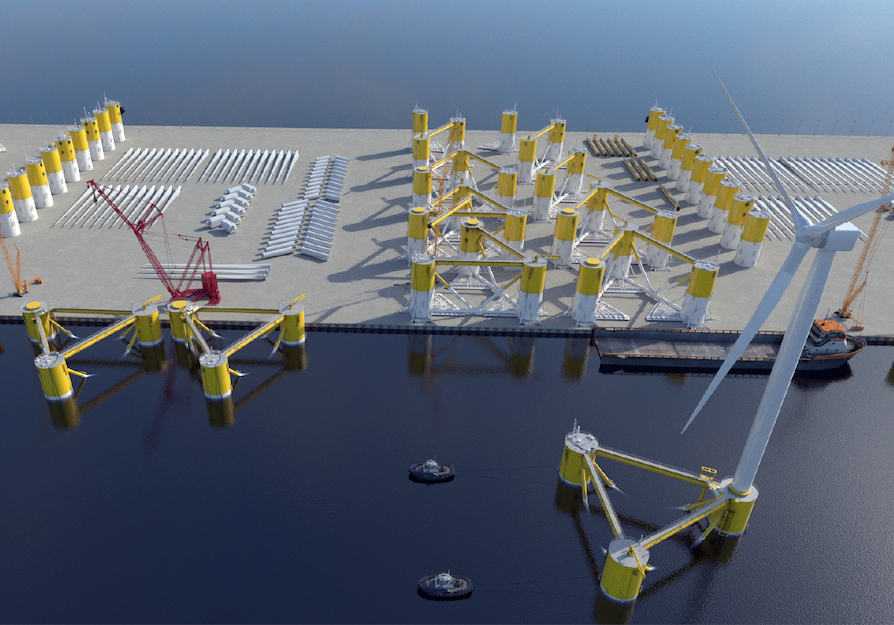

“Existing U.S. port infrastructure is largely unable to (place) offshore wind component manufacturing and project deployment,” McQuillan said.

“In order to meet industry needs, more than 35 new offshore wind projects have gone into development over the last five years,” he continued. “These projects have already employed nearly 1,000 people in professional and trade jobs and are case studies for how the offshore wind industry can create new, family-sustaining careers.”

McQuillan went on to state that unfortunately, most offshore wind projects under development are now facing material financing gaps due to construction cost escalation — which has increased between 30% and 40% over the last three years — as well as the commercial uncertainties associated with supporting a brand-new industry.

“Perhaps now more than ever,” he said, “it’s clear that long-term infrastructure planning and investment are enable sustainable industry growth and the creation of thousands of offshore wind manufacturing, logistics and operations jobs.”

Without additional government funding and policies that support and incentivize private investment into U.S. offshore wind port infrastructure, port capacity will continue to be a major offshore wind deployment constraint across the country, he commented.

Based on an asset-level evaluation of the port developments required to achieve 30 GW by 2030 and create a pathway to the nation’s long-term offshore wind goals, Bardex has estimated that the U.S. needs a total of 99 to 119 port development sites across the West Coast and elsewhere in the country.

About 35 offshore wind port sites and already in development or have recently reached commercial operations, therefore the U.S. is currently facing an offshore port infrastructure gap of 64 to 84 projects, McQuillan stated.

“Funding and building this new domestic infrastructure are critical to enabling the U.S. energy transition and combating climate change,” he said. “Doing so will also help ensure long-term national energy independence and enable the creation of up to 83,000 offshore wind industry jobs across the country.”

Bardex has estimated that the total to address the nation’s offshore wind port infrastructure gap, assuming 2023 construction prices and no financing costs, is between $22.5 billion and $27.2 billion. This construction funding gap is about 3.4% to 6.2% of the total capital needed for project development through 2050, according to the company.

“Put another way, investing in offshore wind port infrastructure will unlock 16-29 times more investment in clean energy generation,” McQuillan said.

He added that in addition to determining the overall port infrastructure funding gap, it’s critical to understand the timing of when this funding is required to be committed and used.

“By utilizing typical distributions of project capital needs over the course of four-to-six-year development timelines and then mapping out when each project is expected to be built, we can assess when infrastructure development capital is required,” he explained.

“After estimating the timing of projects over the next decade and accounting for construction inflation, the upper bound of capital required to address the offshore wind port infrastructure gap escalates from $27.2 billion (2023) to $36 billion ($ year of expenditure),” McQuillan said. “We estimate that financial costs associated with developing these projects would be an additional $7.2 billion ($ year of expenditure) over 10 years.”

The Sacramento offshore wind event was one of a series of summits periodically held by Oceantic across the country. In addition to McQuillan, speakers at the event included Laura Zagar, the San Francisco Office Managing Partner with international law firm Perkins Coie LLP, who gave a talk on the West Coast implications of the floating offshore wind market.

In her remarks, Zagar said that the target amount of offshore wind energy capacity planned to be installed by 2050 on the West Coast is 3 GW in Oregon and 25 GW in California. One GW is roughly the size of two coal-fired power plants and is enough energy to power 750,000 homes.

Nationwide, there’s a total of 12 GW of floating offshore wind projects currently undergoing the permitting process, she said, but none yet under construction.

Mark Edward Nero can be reached at mark@maritimepublishing.com