On Dec. 4, the Coast Guard published a Request-for-Information (RFI) pertaining to vessel response plans (VRP) for western Alaska. VRPs are developed in order to prepare for an oil spill and have to detail both the equipment and resources carried on a vessel as well as shoreside assistance that can quickly respond.

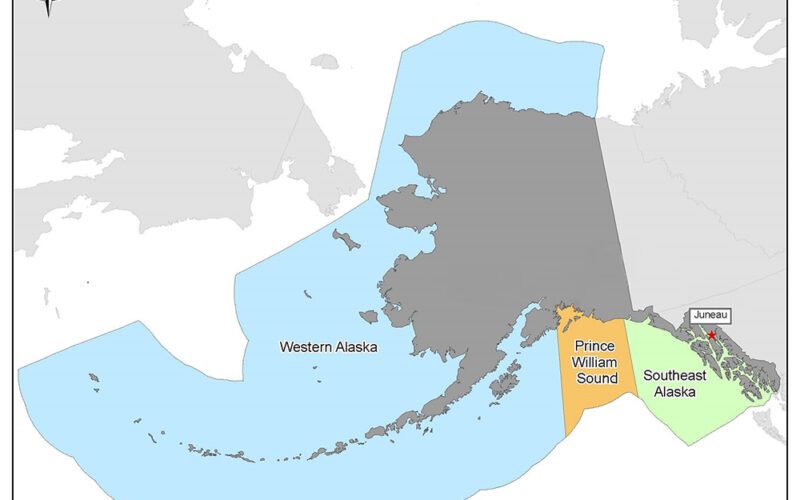

This is a new effort focused on developing distinct response plan criteria for the Western Alaska and Prince William Sound Captain of the Port zones. The criteria must include minimum response times, improvements to wildlife response and consideration of prevention and mitigation measures.

Taken together, the Western Alaska zones form the entire mainland coastline of Alaska plus thousands of additional miles of the coastlines along the state’s major and minor islands.

According to the state, Alaska’s coastline extends 6,640 miles point-to-point; when islands are included, it increases to 33,904 miles. The estimated tidal shore, including islands, inlets and shoreline to head of tidewater, is 47,300 miles.

The Coast Guard’s public comment deadline is March 4. The next steps aren’t clear, but in the RFI text, the Guard writes that public comments would assist in “potentially developing a regulatory proposal to support the mandate.”

Vessel response plans are required to cover all navigable waters of the U.S. in which a vessel operates and are based on NPCs—national planning criteria.

However, alternate planning criteria (APCs) are allowed in remote areas, where adequate response resources are not available, or the commercial resources that are available do not meet the required planning criteria for where a vessel is operating.

In remote areas, the RFI explains, “a vessel owner or operator may request that the Coast Guard accept an alternative planning criteria.” Remote characterizes many of Alaska’s territories and seascapes.

However, APCs have presented a difficult and contentious set of issues for the Coast Guard and the maritime industry. The development and establishment of APCs has a long history, dating back to at least 2009. Progress has been disjointed, moving along on a number of fronts.

In April 2020 for example, the Guard established MORPAG—the Maritime Oil-spill Response Planning Advisory Group—to provide “recommendations for updating VRP regulations and aligning national policy in order to improve program consistency, VRP effectiveness,and streamlined submission and review processes.”

MORPAG also was asked to weigh in on ideas pertaining to alternative planning criteria in remote areas. In background text, the Guard writes that “planning for oil spills and preparing adequate response strategies that meet national planning criteria in remote areas where response resources are scarce is a very complex process that can be confusing without proper guidance.”

MORPAG suggested improvements in eight broad areas, including revised guidelines for oil spill response organizations, defining “equivalence,” i.e., alternate vs. national criteria, so that terms and conditions are less subjective, and enforcing NPC compliance more insistently rather than readily accepting an APC.

The December RFI references two separate efforts: one to advance broader issues pertaining to vessel response planning criteria, i.e., NPCs and alternate planning criteria.

The second is to meet legislative requirements set by the 2022 Don Young Coast Guard Authorization Act, also requiring VRP program criteria, but separate and perhaps different.

In April 2023, the Guard established another group, the Marine Environmental Response Criteria Action Team, tasked with “reconciling” MORPAG’s VRP and APC recommendations.

(Note: it’s unclear from the RFI text whether the two programs would be reconciled and remain separate, or whether “reconcile” means a goal of streamlining the two programs, perhaps by merging them.)

The Coast Guard writes that it will create “planning criteria unique for VRPs in the Western Alaska (Captain of the Port) zone.” The 2022 Act lists seven core issues important for western Alaska. The focus is actually more extensive, though, because the issue pertaining to oil spill removal organizations is broken into eight parts.

The core planning criteria for the Don Young Act include, in addition to the oil spill response organizations referenced above:

- Mechanical oil spill response resources.

- Mobilization response times.

- Availability of emergency vessels.

- Tank barges and on-board emergency equipment.

- VRP expiration dates, and

- Ability to manage wildlife protection and rehabilitation.

Plus, if judged appropriate, planners may reference three additional criteria: vessel routing measures, real-time vessel tracking and whether subregional, separate planning is necessary.

To help build an Alaska program, the Coast Guard seeks information across 16 general topics and related questions, including: should national planning criteria remain the standard? What can best determine realistic response times? How can a plan prepare for expanded Arctic shipping?

As of mid-January there were no comments filed yet in the docket pertaining to the December RFI.

As noted, these VRP developments have a long history and it’s instructive to look back at other recent filings.

After publishing its March 30, 2023 request-for-information pertaining to MORPAG’s vessel response plan recommendations, the Coast Guard received 21 sets of comments from maritime interests. Some of those provide insight into challenges regarding the separate issue of western Alaska.

For example, from the Prince William Sound Regional Citizens’ Advisory Council, a 19-member public body that promotes environmentally safe operation of the Valdez Marine Terminal:

“After living through the devastation of the Exxon Valdez oil spill and its aftermath, no Alaskan would want to see any provisions enacted that would potentially weaken existing standards and/or capabilities that help protect the state of Alaska from another major oil spill.”

The council also suggests that alternate planning criteria should not be granted in areas that have adequate infrastructure to support deep draft vessels and barges, and docks and harbors necessary to support equipment and personnel needed to meet NPC.

“Instead,” the council suggests, “vessel owners and operators in these areas should be required to build capacity to meet NPC.”

The Alaska Chadux Network, an industry-led and funded nonprofit oil spill response organization headquartered in Anchorage, wrote regarding MORPAG’s recommendations.

The network advises the EPA that western Alaska planning criteria should, indeed, consider MORPAG’s suggestions, but next steps need “input from key stakeholders and MORPAG recommendations should not diminish comments from Alaska state and local governments, Tribes, the vessel owners and operators that would be subject to planning criteria, oil spill removal organizations, Alaska Native organizations, and environmental nongovernmental organizations, as called for in the new (Dan Young) legislation.”

The network suggests four key steps for western Alaska planning, to:

- Require vessel tracking and monitoring.

- Avoid double-counting of oil spill response and salvage marine firefighting functional requirements.

- Reject subzones “which are bad for Alaska” and create patchwork requirements and cause abandonment of spill preparedness in low-traffic areas, and

- Locate equipment in Alaska and not “rely on equipment in the Lower 48 that would need to be ‘cascaded’ into the state and result in delays in being delivered to a spill incident.”

Finally, comments from the Ocean Conservancy also indicate that officials there have an eye on the future, i.e., aligning the Don Young requirements with current programs.

“Ensure clarity regarding the relationship between the APC issue broadly and the forthcoming Western Alaska oil spill planning criteria program,” the organization wrote.

The conservancy also notes the Coast Guard’s long-time struggle to implement alternative criteria in Alaska, particularly for non-tank vessels. Regarding western Alaska, its comments are cautionary:

“There is significant potential for confusion regarding the geographic areas affected by current APC policy, the MORPAG recommendations (which reference area committees), and the forthcoming Western Alaska planning criteria program. We take this opportunity to emphasize that it will be of the utmost importance that future USCG communications clarify the relationship between the Western Alaska oil spill planning criteria program and any updated guidance regarding APCs or VRPs nationally that may result from the MORPAG process.”

“Put simply, regulators, plan holders, oil spill response organizations, Tribes and other interested parties need to know which rules will apply in which geographic regions of Alaska,” Conservancy officials added.

The Don Young Act gives the Guard two years to establish western Alaska planning criteria. There will be continuing developments this year.

Tom Ewing is a freelance writer specializing in energy, environmental and related regulatory issues.